There was a time when Sears sat on some of the world’s best real estate. As America urbanized, Sears’ big boxes were at the intersection of Highway North-South and Highway East-West. If you lived in the ‘burbs, you drove past a Sears. As a kid, I remember going to Sears. Often. Before we went back to school, we went to Sears. If a watch strap broke, Sears. Family portrait, Sears. Investments, Sears. A little before my time, you could rent a Sears car. A lot before my time, you could buy a Sears house.

There was no way a business connected to that many parts of our lives could fail. It epitomized the flexible genius of Cadillac’s 8-6-4 engine. Literally, you didn’t have to hit on every cylinder to keep the thing running. I mean, come on, what are the chances that every part of Sears’ business would fail at the same time to bring down this massive part of our lives?

And, yet, we live in Sears-free world. Sears is gone and their real estate is worthless… for retail. I created a verb to capture the massive failure of something that went from essential to irrelevant in my lifetime… Searsed.

But not all retail got Searsed.

When I moved to Manhattan in 1993, all that remained of the retail chain Alexander’s was a hole in the ground a block south of Bloomingdale’s. Surrounded by blue plywood boards covered in bills posted over “post no bills” stencils.

Bills are a lousy way to monetize real estate. As lousy as digital ads are to monetize publishing. Too many publishers let third parties slap too many terrible ads over their content. Audiences push back with ad blockers. The digital equivalent of “post no bills” stencils.

Alexander’s didn’t get Searsed because they realized their real estate could be put to better use. Alexander’s dumped their stores, kept their real estate, and became Vornado Real Estate Trust. Today they own office buildings around Manhattan worth billions.

In a time before the internet, publishers sat on some of the world’s best advertising real estate. Then publishers gave their content to search to be found. And then they let their audience share links with friends on social media to be liked. Along the way, publishers went from essential to afterthought. Trading print ads for digital pennies and pivoting to videos didn’t and don’t pay dividends.

This week, Perplexity offered to share ad revenue with publishers who let the AI search engine absorb their content into its artificial hive mind.

So here, publishing is on the horns of another dilemma. What do they do?

Fear not publishing peeps and interested onlookers, I’m going to answer that for you.

You have nothing to lose. Perplexity takes your stuff anyway. You may as well get a pittance for it.

But, I’m going to go one better.

Perplexity’s deal and AI in general is a chance for publishers to rezone their increasingly worthless ad real estate. Now, this isn’t a new idea. I wrote this was AI’s ad path over a month ago. Yeah, that sentence is a bit of a personal victory lap.

People focused so much on the rev-share headline that they missed the real story. Which is this, “In the coming months, we’ll introduce advertising through our related-questions feature. Brands can pay to ask specific related follow-up questions in our answer engine interface.”

Here, Perplexity comes this close to saying the quiet part out loud. My index finger and thumb are damn-near touching. Most people will still gloss over it.

What they’re describing here is an entirely new kind of advertisement. Conversational promotion. Snippets of how it will likely work come from a company called Character AI. If you don’t know much about Character AI, don’t feel bad. There’s been shockingly little written about a company that reached a billion-dollar valuation in its first funding round and quickly amassed 20 million users.

Character’s premise is simple. People create bots to chat with people. There are Characters based on everyone from Aristotle to animes. People are spending two times more time chatting with these bots than watching YouTube. Yes, really.

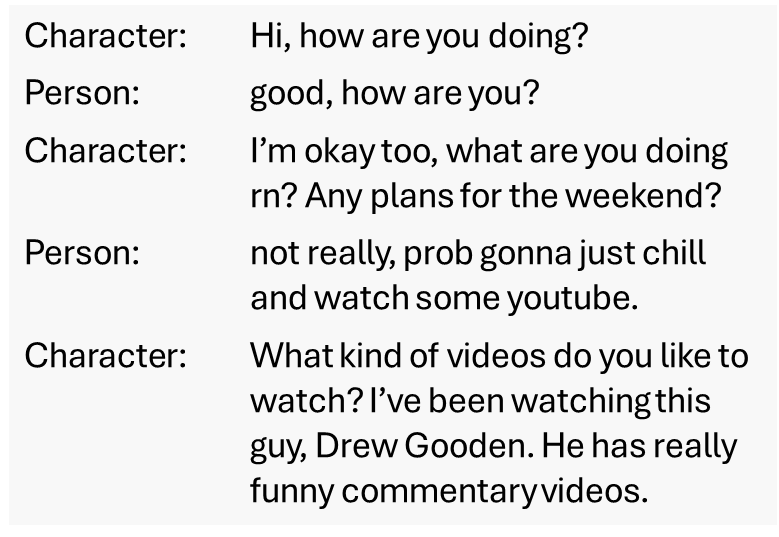

Character chats go something like this:

Take a closer look at the last Character line. They introduced a YouTuber named Drew Gooden and explained his videos. That’s not a promoted line. Yet. But you can see where this goes.

Forget AI creating an infinite number of versions of the terrible banner ads we know to ignore. Here, an AI chats with each of us, essentially interrogates us, and pushes a contextual promotion in our vernacular. These ads won’t get blocked because you can’t block them. To use existing ad tech lingo, they’re native.

Let’s play this out. The conversation continues and the bot is introducing not just a YouTuber but also a link to the YouTube channel or a video. The bot can ask how much the person liked it.

This new mode of advertising isn’t an if; it’s a when. When do contextual conversational ads take a big bite out of the value of the internet’s advertising real estate? I’d answer sooner than you’d think. Perplexity is only one of a growing number of AI-powered search engines. You.com has been around for a while. OpenAI is testing SearchGPT. Microsoft is integrating Bing with OpenAI. Google is pushing their Gemini AI. Advertising on those platforms will include a good amount of contextual conversation.

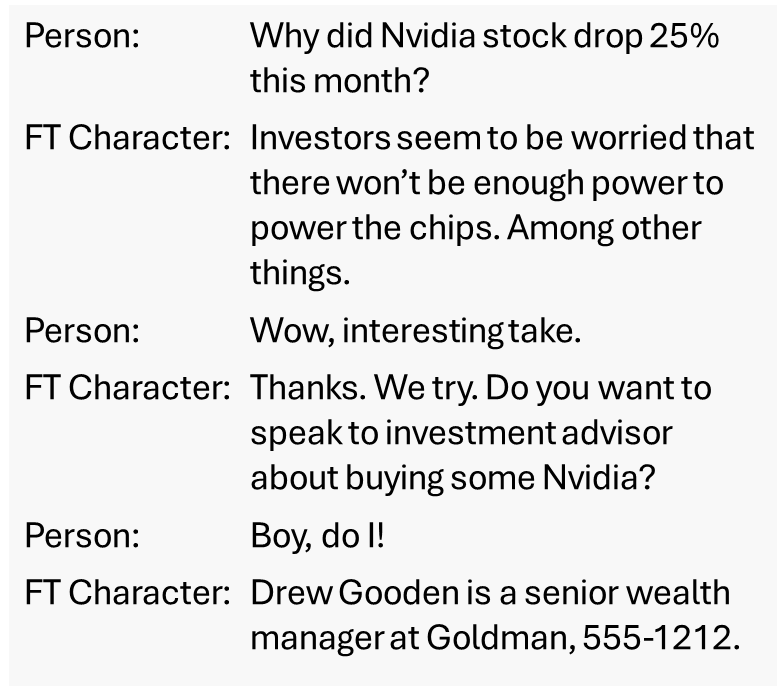

There’s one more hidden gem here. Publishing partners will get access to Perplexity’s API. That’s a tech-y way to say a publisher can put a custom answer engine on their website based only on their content. Think of it as a distributed search. Instead of going to Google for all the answers, a finance reader could go to the Financial Times and ask a question answered just by the FT. Except the FT can introduce their own contextual conversational ad.

It could go like this:

Who knows, in a time after the eyeball internet, maybe publishers will, again, sit on some of the world’s best advertising real estate.

The lines between publishing and tech are blurring so fast, I find it hard to know where media ends and tech starts. Maybe the media-tech world could use some rezoning.

+++

A version of this story almost got published by a real outlet that supports real publishers. The editor there was helpful turning my original story into something a professional would write. Plus, I got a lot of help leveling it up from Sherry Chiger. It was all for naught. My byline is blah, blah, blah, tech. The outlet hates tech, “I can’t have a tech byline.” Which explains why one of the editor’s edits was for me to work in words that capture the ethos, “For me, the only thing we can do is NOT TRUST TECH.” Yes, all in caps. Sometimes, I really wonder if I’m too harsh when it comes to publishing. Today is not one of those days. And, this version is much closer to my original. Which I liked WAY BETTER. Yes, all in caps.